The Sunday Times — Escape from Kabul: the female students who fled the Taliban

Posted on December 16, 2021

Written by AUW

Escape from Kabul: the female students who fled the Taliban

As the Afghan capital fell, 148 women made an astonishing bid for freedom, tracked from the US via their phones

The students on board a US military transport plane

Sunday December 12 2021, 12.01am GMT, The Sunday Times

https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/kabul-afghanistan-taliban-female-students-escape-96sqvkhxc

It was one o’clock in the morning outside Kabul airport and Sepehra Azami, 25, was crammed into one of seven buses carrying female Afghan students desperate to flee the country. Thousands of people thronged the streets and fear filled the air. Taliban fighters dressed in black turbans and camouflage jackets roamed around toting Kalashnikovs. Hours earlier the blast from a suicide bomb had ripped through the crowd, killing 13 US soldiers and more than 150 civilians.

Terrified families were now trying to claw their way inside vehicles, including the girls’ buses, hoping to escape. Sepehra watched as a young woman disembarked from one bus full of young students and began to beg the Taliban fighters to let them through the airport gates.

“The Talib spat, ‘You’re a woman and you think you can come and talk to us?’ ” she recalls. “Then he started shooting at her feet.” The woman scrambled back on board and the other students began to panic. There were 148 of them in total, aged from their teens to early twenties, with not a single seat to spare. They were exhausted and frightened. None of them had experienced Taliban rule, but they’d heard stories from their mothers and grandmothers about the group’s hardline version of Islamic law, effectively forbidding female education.

In a bid to avoid scrutiny, most of the students had put on the all-encompassing burqa, a garment alien to them; others made do by swathing their bodies in long, winding dupatta scarves. But here, on August 27, were the Talibs, bearded, armed and menacing, right outside the bus windows — and the students were begging Sepehra to tell them what to do.

US Marines assist in the evacuation at Kabul airport on August 21, days before the deadline

AP

“We were in the middle of the road surrounded by Taliban with guns in their hands and I was responsible for them all,” she says. “I have to make the decision. We either take another risk and try once again to get into the airport or we have to go back home and we might be stuck in Afghanistan for ever.”

Sepehra, raised in a poor household in the rural north of Afghanistan, had never faced such a dilemma before. Each of the seven buses had been assigned a group leader. Mature beyond her years and quietly determined, Sepehra was already a student representative at the university, now in her final year. Suddenly the fate of dozens of her fellow students was in her hands.

“I had not slept for days,” she says. “I was unarmed. I thought anything could happen.”

She had only one option for help: Dr Kamal Ahmad, the head of the university where students were studying. She called him: it was late but he’d been awake all hours helping the students to escape. “I have been happy to call the shots up until now,” Sepehra told him. “But now it’s clear this is about life or death and I’m not prepared to decide for them. Do you want us to stay or turn back?”

Dr Kamal Ahmad, founder of the Asian University for Women, based in Bangladesh

JON ATTENBOROUGH FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES MAGAZINE

He told them to go home. “I was so devastated,” Sepehra says. “What if we could not make it again?”

There were still two days before the deadline imposed by the Taliban on Afghans leaving Kabul, though. The students still had a chance — if they were willing to brave the chaos of the airport once again.

‘Fill them with dreams’

The young Afghan women stranded on the buses outside Kabul’s airport that night were students and graduates of a remarkable university in Bangladesh to which they were trying to return. The Asian University for Women (AUW) in Chittagong had plucked them from humble backgrounds in Afghanistan to give them an education and create a new generation of female leaders. Ahmad, a Harvard graduate and former director of a Unesco task force on higher education, founded the university in 2008 with funding from private philanthropy, including grants from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and academic partnerships with Johns Hopkins and the University of Sussex. Today, Cherie Blair is its chancellor and Laura Bush, the former US first lady, one of its patrons.

“The idea was to find young women of extraordinary strength and resilience from unexpected settings,” he explains. “Give them an education and fill them up with dreams, as well as work on actualising those dreams.”

Ahmad wanted to offer a university education to girls who might not even have all the necessary secondary schooling. He initially recruited promising students from across Asia, from the villages of Nepal to far-flung East Timor. When he set out to add students from remote areas of Afghanistan, where where deeply conservative attitudes were a far greater barrier to girls’ ambitions, he was warned it would be a particular challenge.

“Everyone said I was wasting my time,” he says with a chuckle. “Even if the students were prepared to come, their parents would not let them or neighbours would object. It was made out to be impossible.”

His first breakthrough came when an influential headmaster from a highly regarded community-run high school in Kabul sent his daughter to AUW; then later he discovered that mobile telephone companies in Afghanistan kept separate records for female and male customers. “We said, we are going to blast these female cellphone subscribers with messages, saying, if you know of a young woman who has courage, who is outraged at injustice and who is compassionate and is eager to learn, to get to university, there is a place looking for her,” he says.

Sepehra was one of those people. Though she came from a modest background, her mother encouraged her to study. A cousin told her about AUW, advising her to apply otherwise she might never escape rural Afghanistan and “will have to get married or stay your whole life inside the home”. In 2019 she was among more than 150 Afghans who made the journey to the campus in Chittagong. She went to study economics, which she hoped to put to good use developing Afghanistan’s stunted manufacturing base on her return.

“Getting the scholarship made such a huge difference in my life,” she says. “It opened my eyes. All these people with different perspectives and mindsets, I had never experienced anything like it. My freedom there compared with back in Afghanistan is like night and day. Because freedom to me means having the chance to know yourself and find out what you are capable of.”

Another of the recruits was Diana Ayubi, who had been born in 1998 and named after Princess Diana, who had died the year before. As an infant she had moved with her parents to Pakistan when the Taliban began shutting down girls’ schools after seizing control in 1996. In 2015 they decided to return home so that Diana could qualify for university, which she would not be allowed to attend for free as a refugee in Pakistan. Then a friend told her about AUW and she applied; she was thrilled by the freedoms she found there. While studying public health, she joined clubs for film, culture and photography, and took lessons in badminton, discovering she had a talent for the sport.

Diana, left, and Sepehra in Syracuse, New York state, after their evacuation

STEPHANIE DIANI FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES MAGAZINE

The students’ new horizons, however, were abruptly curtailed in 2020 by the coronavirus pandemic. As Bangladesh imposed a nationwide curfew and international borders closed, Ahmad took the decision that it was safer for the young Afghans to return home to pursue their studies remotely. All but a handful left.

The Taliban return

As Sepehra and Diana returned home, the Taliban were gaining control of the country once again. They had been gathering strength in Afghanistan’s rural south for years, bringing their iron rule to villages, but were now making disturbing headway in the north as well. On February 29, 2020, President Trump’s administration had signed a peace agreement in Doha under which the Taliban agreed not to attack American troops in return for a US promise to withdraw its forces from the country the following year.

Time, though, was already running out. About an hour after the meeting the students received a voice message from one of their group in the city centre. “She was running so fast and she was saying, ‘Please don’t go outside, go to your homes because Taliban have come.’ The other girls said, ‘OK, stop, don’t spread these rumours.’ And she said, ‘I’m sorry if I upset you but this is the truth. The Taliban are here.’ ”

Faster than anyone had expected, the Taliban had advanced on the capital and were seizing control. “Just like that everything changed,” Sepehra says.

Diana rushed through the panicked streets to get home, stopping only at a shop to buy credit for her phone so she could stay in touch with the group. But all the phone cards had already been sold, leaving the shop bare. Banks had closed their doors and huge queues formed beside rapidly emptying cash machines.

“There was nothing left,” she says. “In one hour we had gone back 20 years.” She thought her home would be safe because a senior Afghan army general lived next door, “but right there, in front of our house, I saw the Taliban for the first time with my own eyes”. The armed man had long, unkempt hair and a fixed stare that raked over her. “It was like looking at someone who was not human,” she says. “I could not see a human being there.”

Ahmad’s plans to charter a flight were fast unravelling as profiteers scented desperation and the cost of exit soared. Private operators were now asking $1 million for a small plane. Scammers tried to lure him into wiring $365,000 for a charter that didn’t even exist. Soon only military flights were operating.

Both Afghans and foreigners who were cleared for passage out of the country were struggling to reach the airport through the Taliban checkpoints. Ahmad turned his attention to finding buses with drivers willing to navigate the streets, organising the students into seven clusters based on their location in the city, each with a student representative in charge. The women would later be dubbed “the Seven Sisters” and “the Magnificent Seven”. All but Sepehra had already graduated.

Taliban fighters at Kabul airport

AP

“I’m in Bangladesh at this point, we don’t have any staff in Kabul,” Ahmad recalls. “We have these drivers, who are not necessarily enthusiastic about taking these girls. So these incredible seven young woman would have to carry all the pressure.”

On the evening of August 23, Ahmad contacted the seven leaders and told them to assemble their groups. “I asked them to each put on a full burqa and urged that they not wear any lipstick,” he says. Most of the girls did not even own a burqa, the enveloping blue cloak compulsory under the Taliban’s previous reign. Diana had to wear a hijab instead. The students said goodbye to their families, and Diana was shaken by the menacing gaze of the Taliban fighters she passed on the streets, “but no one threatened us or tried to stop us”.

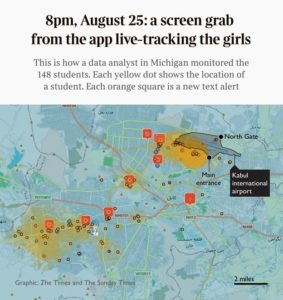

Andrew Schroeder, a data specialist in the US who was working with AUW, had instructed all the students to download a tracking app to their phones so he could keep account of them individually. He monitored their positions from his home in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Little yellow dots on his computer screen showed where each student was setting out from. Orange squares showed the positions where messages from the student leaders were coming from. Gradually he saw the yellow dots coalescing around each square, then the squares making their way along the roads to the airport.

Ahmad had made contact with the US military commanders guarding the gates to co-ordinate the girls’ escape. Still believing he would be able to get a charter flight in to fetch them, he was told to direct the buses to the South Gate, the airport’s main entrance in more normal times. Then, just as the buses approached the gate, a US military co-ordinator sent another message. “He said, ‘If you come, you are endangering yourself and you will endanger others. In any event if you come to the South Gate, we will turn you around.’ I wasn’t going to challenge that. So we asked all the seven buses to return,” Ahmad says.

The military told Ahmad he needed to give them 24 hours’ notice of the students’ arrival. What they didn’t divulge was that intelligence had picked up a credible threat of a planned suicide attack at one of the airport gates.

The next afternoon, on August 25, the students gathered to try again. After negotiating their way through more than a dozen Taliban checkpoints, they once more reached the South Gate. But higher-ranking Taliban commanders refused to let them pass. They turned and headed for the North Gate, controlled by the US military and Nato troops, and waited on board the buses. Hours later Ahmad emailed the Americans to ask what was happening. Eventually they redirected the students back to the South Gate to try to gain entry there. In the chaos the buses lost their way. From thousands of miles away in Ann Arbor, Schroeder helped them to navigate.

At about 6pm they were waiting a little distance away from the gate when a suicide bomber — later claimed to be from the Islamic State militant group — detonated an explosive belt, the blast ripping through the crowds of men, women and children. The shock waves rocked the buses and havoc erupted as both American and Taliban fighters opened fire. “They were firing and firing and it was so close to us,” Diana says. “It was terrifying.”

In the confusion she became aware that the driver was trying to smuggle some people on to the bus in the apparent hope they would get inside the airport. “I was sitting behind the driver and I could see what was going on,” she says. “They were trying to break into the bus.” A skirmish broke out, while the students pleaded with the drivers to keep the doors shut.

By this time the girls had been awake for more than 36 hours. “Everyone was tired, everyone was hungry and thirsty,” Diana says. “Some of the girls’ families were calling them and saying, ‘Come home, don’t take the risk.’ And others were saying, ‘Don’t come home, it’s more risky than being at the airport.’ ” It was now that Sepehra called Ahmad, who told them to go home.

Snap decision

Later that day, August 27, Ahmad and the students decided they would make one last attempt to get out. In the wake of the suicide attack the Americans had forbidden anyone from bringing luggage, so they would have to leave in the clothes they were wearing, with nothing extra but their phones. For a few of the students that was the moment they felt overwhelmed.

“You forget they are just teenagers in this situation,” Ahmad says, “and that this is an unimaginable thing you are asking of them.” Zuhal, one of the students, texted Ahmad to say she’d had no dresses to wear when she arrived in Bangladesh and no money to buy any, and she begged to be allowed to bring some luggage. “I can’t stop crying,” she wrote. “Sir, please give me permission, please sir.”

He told her: “Get on that plane and I will buy you five dresses when you are here.”

When the students assembled for their buses, about 25 were missing. Messages to their phones went unanswered. As Ahmad later discovered, they or their families were too frightened for them to risk going to the airport again. With 20 minutes to go, Ahmad had a choice to make: let the buses leave for the airport with precious empty seats or find others to fill the spaces. He told any girl with sisters of university age to join them so that no seat was wasted. He vowed to find a way to admit them to the university. “That is the kind of person you want, after all,” he says, “someone with that kind of courage.”

Sepehra saw a chance for her sisters, Sareshta, 22, and Saruda, 21. Both were students at university in Kabul but their future had been thrown into jeopardy after the Taliban took over, separating male and female students and cancelling courses. “I was really worried about their safety,” she says. She feared they would be forced into marrying Taliban fighters. Now they had a chance to escape with her. Sepehra spoke to her parents and received their blessing for her sisters to join her on the bus.

Charter flights had now been forbidden from landing. The girls’ only hope was to get on board a US military aircraft. They were lucky: the Taliban, after negotiations with the Americans, were no longer preventing people from entering the airport.

The students finally board a US military plane

At the last of the checks, a Taliban fighter leafed through Diana’s passport. “Your name is not Islamic,” he said, “so now you are going to your country.” As they walked towards the American soldiers, one Talib shouted: “You are going and you may be happy, but remember you will never be allowed back.” The students lined up in a snaking queue leading into a cavernous military transport plane. “There were no seats, we were all sitting on the floor,” Sepehra says. “And when I looked at each one of the students’ faces, most of them were crying. They were thinking, ‘OK, we are safe, but where are we going to go?’ ”

Where have they gone?

In Ann Arbor, Schroeder saw his tracking dashboard go dark as the plane took off and the students’ phones went out of network range. Dark, that is, except for three lights still flashing at Kabul airport. Schroeder thought there must be a mistake. In Bangladesh Ahmad received a panicked message. Three of the girls, mindful of his exhortation to keep their phones on at all times, had gone to find somewhere to charge them. Overcome with stress and exhaustion, they’d fallen asleep and woken in a panic to find their classmates gone. Thankfully they managed to track down an American soldier to tell them what had happened and then called Ahmad to explain.

Neither Ahmad or Schroeder had any idea where the rest of the girls were heading. They advised the three girls left behind to board the next military flight to Qatar, where most of the evacuation flights were bound. The trio arrived in Qatar a few hours later and were taken to a hangar. There was no sign of their classmates.

On the first flight, Diana remembers the plane landing and one of her friends’ phones lighting up with a roaming alert. “We’re in Saudi Arabia!” she exclaimed. They had arrived at a US military base outside Riyadh. The next morning they had their fingerprints taken and their passports processed. An American official offered Diana his mobile phone to call her family, adding that she could tell them she was alive but not where she was.

Though safe, the women are exhausted and distressed at not knowing their destination

“So I called my mother and when she heard my voice, we both cried for one minute straight,” Diana recalls. “The man was saying, ‘You need to hurry up, other people have to call their families too.’ And I said, ‘Mum, I am safe, I am alive but they may take us to America, so don’t be surprised, but I am pretty sure it won’t happen and I will be going back to Bangladesh.’ ”

They weren’t going to Bangladesh. The next evening they were put on another flight and given no information about their destination. They landed the following morning and once again a phone lit up with an alert: now they were in Spain. “I called my sister and said, ‘I am in Spain now!’ ” Diana says. “And she said, ‘Seriously, the Spain that’s in Europe? Wow.’ ”

At the Spanish airbase, the three who had been left behind in Kabul were reunited with the others and they were all told to prepare for one more journey.

This time they boarded a commercial flight. Diana checked the seatback screens and saw that their plane was going to Washington. “Then I knew that seriously I am going to America,” she says. “So I closed my eyes and fell asleep.”

The students were flown to Wisconsin, where they boarded buses for Fort McCoy, a military base. Having thought they were returning to a new term in Bangladesh, they now found themselves among thousands of other Afghan evacuees in a refugee camp thousands of miles from home.

From the moment the students landed in Riyadh and Doha, they entered the US resettlement system. Ahmad had initially made frantic inquiries from Chittagong as to how he could reroute them to the university. But it swiftly dawned on him that his ability to protect them might not extend beyond graduation if the Taliban remained in power in Afghanistan, leaving them stranded and effectively stateless in Bangladesh. With no other option that would ensure their long-term safety, the decision was taken to resettle the students in America.

“I was not expecting to come here,” Diana tells me on a shaky video connection from Fort McCoy, a complex of accommodation blocks that once housed Japanese prisoners during the Second World War. She is still traumatised by the unexpected rupture from her family, though grateful for her chance at a new life. “I can’t express what might have happened to us if we had not escaped,” she says. “For everything I have received from the US, I am so, so thankful.”

She looks around as other girls pass by. “I can see that they are smiling, they are happy, they are enjoying walking outside. They may not be smiling inside, but they are sure they are safe here.”

At first the students were in mixed blocks with other evacuees, including young Afghan men who verbally harassed them for wearing jeans and no headscarves. Eventually they complained to the camp officials, who brought them all together in their own separate building.

Sepehra noticed there were lots of children at Fort MCoy “with nothing to do, just fighting with each other”. The students were also at a loose end, unable even to join their online classes with AUW because of the lack of good wi-fi. Sepehra went to the head of the base and asked if the students could organise classes to teach English.

Sepehra set up classes for other refugees

“When parents heard about the school, they started to bring their children,” she says, “and then some of the women wanted to start learning too.”

Eventually they began holding classes for older boys and men, including those who had previously harassed them. “They are learning now that men and women are equal,” Sepehra laughs.

No going back?

After the students arrived in Wisconsin, Ahmad called on AUW’s network to help find places for them to continue their studies. Sixty-eight students have now been awarded fully funded places at Arizona State University. After a short stay in Syracuse, in New York state, Sepehra and Diana recently arrived at the nearby Cornell University, an Ivy League college where eight AUW students have been granted full scholarships.

Since fleeing with her two younger sisters, Sepehra has faced the wrath of family and friends back in Afghanistan; they are resentful that she could not take more of them out. Her youngest sister, Saroba, 13, is now stuck at home after the Taliban issued an edict effectively banning girls from secondary school education. “She’s not OK,” Sepehra says. “I’m trying to give her hope and I’m encouraging her that this nightmare will end one day, but we both know it won’t be easy.”

Diana, left, and Sepehra have places at Cornell University in New York state

STEPHANIE DIANI

Diana remains haunted by the Taliban’s last words to her, that she could never return home. “They know who we are now,” she says. “Everything is messed up. I don’t think that in 10 or 15 years there will be the same Afghanistan that we left.”

Back in Chittagong, Ahmad has set about persuading the Taliban to allow more Afghan girls to come and take the place of the students who didn’t make it back to Bangladesh. In the past few months he has received about 3,000 applications; he has funding for 170 places. For now there are just three Afghan students in Chittagong — the ones who stayed put when the pandemic hit. They lead a very different life from that being imposed by the Taliban back home, including wearing lipstick whenever they choose. It’s a reminder of how Ahmad instructed the students in Afghanistan to “shed their lipstick for the journey” when they first tried to escape.

“Lipstick took on more meaning to me at that moment than I ever imagined it could,” he tells me. While he was making plans for the girls’ return, the university bought a lipstick for every student expected from Afghanistan. But they never arrived in Chittagong, finding instead a new future elsewhere. So now the lipsticks are on display at AUW “as a small remembrance of our Afghan students.”